RPE vs Heart Rate for Trail Running: Why Perceived Effort Wins in the Mountains

When you're grinding up a 600 metre climb at 64km of a mountain ultra, your heart rate monitor might read 155 bpm: the same number it showed during your easy morning run last week. But your legs are screaming, your breathing is laboured, and you know these two efforts couldn't be more different. This disconnect is precisely why Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) becomes the superior training metric for trail and mountain running. This post is here to explain what RPE is, and why we use it as a metric for training.

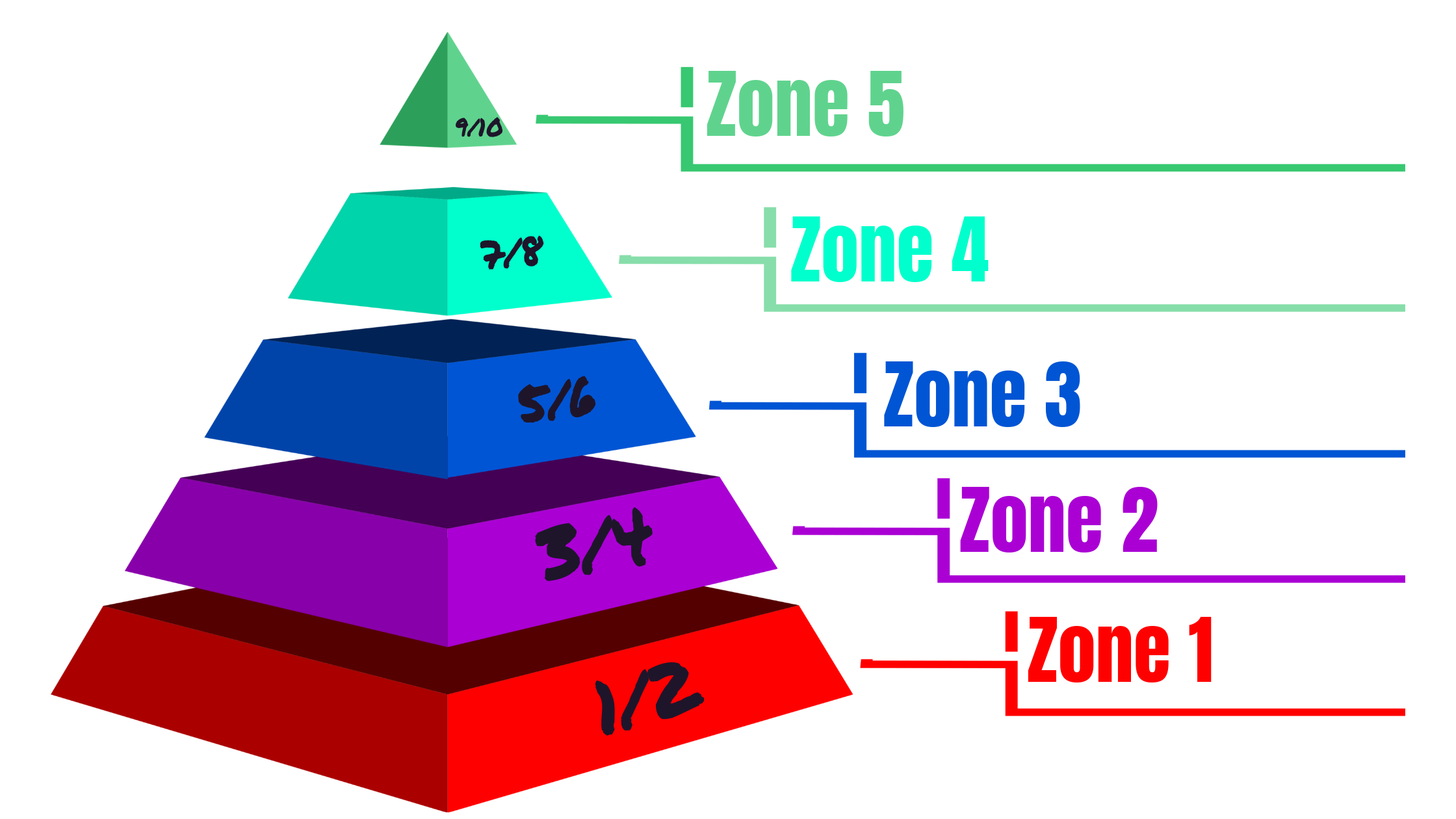

RPE is your subjective assessment of effort intensity, typically measured on a 1 to 10 scale where 1 is standing still and 10 is maximal effort. But for trail runners, RPE functions as something more sophisticated than simple perception. It's an integrated output signal that accounts for every variable your body is experiencing in real time.

This is a great visual of roughly how you can translate 5 conventional zones to an RPE effort. The longer your race the more this can vary.

Quick Summary

Don’t have time for the full read? Here is a quick summary to understand the key differences

RPE works better because: it integrates cardiovascular strain, muscular fatigue, and environmental factors into one real time output signal. For example at mile 160 of Wild Horse it felt like a 9/10 effort, but the HR data would put me in zone 2. which is a better indication of how hard the work is being completed? It also teaches the internal regulation skills essential for ultra pacing when conditions deviate from plan.

Heart rate training breaks down in mountains because: cardiac lag creates a 30 to 90 second delay on variable terrain, making HR a historical record rather than current effort indicator; muscular damage from technical descents doesn't register in cardiovascular data; altitude elevates HR 10 to 20% independent of actual effort

Implementation: Structure training around RPE targets (easy days at 3 to 4, tempo at 6 to 7, long runs at below 5) and let terrain create natural variation. Use HR for post run analysis and tracking trends, but regulate effort in real time by perceived exertion.

Where Heart Rate Training Falls Apart in the Mountains

Heart rate training works reasonably well on flat, predictable terrain where cardiovascular demand correlates tightly with effort. But mountains break this relationship in multiple ways that matter for training specificity.

Cardiac Lag on Variable Terrain Heart rate responds to effort changes with a 30 to 90 second delay. On technical trails where you're constantly shifting between steep climbs, technical descents, and flatter sections, your HR data becomes a historical record rather than a current effort indicator. You'll routinely see your heart rate peaking during recovery sections simply because it's still catching up to the previous climb. This lag makes it impossible to accurately dose effort in real time when terrain changes every few minutes.

The Muscular Load Disconnect A technical descent might keep your heart rate at 130 bpm while absolutely destroying your quads through eccentric loading. Heart rate reads this as "easy effort" when the muscular damage and glycogen depletion are substantial. Conversely, hiking steep grades with poles can put your heart rate into zone 4 or 5 while the muscular demand remains aerobic and sustainable. RPE captures both cardiovascular and muscular strain simultaneously—a 6-7/10 effort on a descent accurately reflects that you're working hard even when HR suggests otherwise.

Altitude's Confounding Effects Above 1,800 metres, your heart rate elevates 10 to 20% for the same absolute workload due to decreased oxygen availability. Run a section at 3,000 metres that would be 145 bpm at sea level, and you might see 165 bpm instead. If you're training by HR zones calculated at sea level, you'll either dramatically underpace your effort or redline trying to hit prescribed numbers. RPE automatically adjusts. A 5/10 conversational effort feels the same whether you're at 600 or 3,000 metres, even though the corresponding heart rates are completely different.

Environmental and Fatigue Factors Heat, cold, dehydration, accumulated fatigue, poor sleep, and inadequate fuelling all elevate heart rate independent of actual training load. In a hot trail marathon, your heart rate might read 170 bpm at a 9/10 effort in the first hour, then 170 bpm at a 7/10 effort in hour three as heat stress and dehydration compound. Training by HR zones in these conditions forces you into either chronic overtraining or confused effort targets. RPE remains reliable because it reflects your actual capacity in that moment.

Why RPE Creates Better Trail-Specific Adaptations

The goal of training isn't to hit specific heart rate numbers. It's to apply appropriate physiological stress that drives adaptation. For trail runners, this means preparing your body for the specific demands of mountain terrain: sustained climbing, eccentric loading, technical focus under fatigue, and variable intensity.

When you train by RPE on trails, you're automatically matching effort to terrain in ways that build course-specific fitness. An easy run at RPE 3-4 will naturally include harder cardiovascular efforts on climbs (where you're building sustainable climbing strength) balanced by muscular recovery on descents. This variable stimulus is exactly what you experience in races, making your training directly transferable.

Heart rate training, by contrast, often forces you into counterproductive pacing decisions. To keep your HR in zone 2 on a climb, you might slow to a crawl that no longer provides adequate stimulus. Or you push harder on descents to maintain zone 2, adding unnecessary impact stress when you should be recovering. RPE lets terrain dictate natural effort variation within the appropriate overall intensity.

Practical Implementation for Mountain Training

For trail runners, a well calibrated RPE scale should map roughly to: 1 to 2 is walking or very easy jogging; 3 to 4 is comfortable conversational pace; 5 to 6 is moderate effort where conversation becomes choppy; 7 to 8 is hard but sustainable; 9 is very hard, race effort; 10 is all out sprinting. The key is that these descriptions remain constant regardless of terrain, altitude, or environmental conditions.

Structure your training weeks around RPE targets rather than HR zones. An easy day might be 90 minutes at RPE 3 to 4, which will include natural variation as terrain changes. A tempo session could be 3x15 minutes at RPE 6 to 7 with 5 minutes easy between, executed on rolling trails where you're learning to maintain consistent effort despite grade changes. Long runs at RPE 4 to 5 teach your body to sustain moderate output for extended duration while accommodating terrain variation.

The critical skill is learning to honestly assess effort independent of pace or external metrics. This takes practice and requires temporarily ignoring your watch's pace feedback. Over time, most runners develop remarkably accurate RPE calibration. Research shows experienced runners can estimate effort within half a zone of laboratory measured intensity.

When to Keep Heart Rate in Your Training Arsenal

RPE should be your primary training metric for trail running, but heart rate data still provides value for specific applications. Post-run analysis of heart rate drift during steady-state efforts can indicate fitness improvements or inadequate recovery. Resting heart rate trends reveal overtraining or illness. And for new runners still developing RPE calibration, cross-referencing perceived effort with HR helps build that internal awareness.

The ideal approach uses RPE for in the moment effort regulation while reviewing heart rate afterward to validate that your perceived efforts align with physiological responses. If you consistently rate a run as RPE 4 but see an average HR at 90% of max, something's miscalibrated. Either your zones, your RPE assessment, or your recovery status needs attention.

Building the Trust to Run by Feel

Letting go of rigid heart rate targets can feel uncomfortable for data-driven runners. There's security in following prescribed zones, even when they don't match terrain realities. But trail running demands adaptability and situational awareness that external metrics can't provide. RPE develops the internal monitoring skills that translate directly to race execution, where you'll need to pace by feel across changing conditions without constantly checking your wrist.

The mountain environment itself teaches RPE calibration better than any lab test. When you've learned what sustainable effort feels like during a four-hour climb, when you understand the difference between working hard and working too hard on technical descents, you've developed an internal regulator far more valuable than any device. That's the training advantage that will carry you through ultras when conditions inevitably deviate from plan.